A year or so back I made brief mention of an historic local individual who, I firmly believe, warrants and deserves a far higher degree of attention from local Socialists than is presently the case.

I refer to George Markham Tweddell - a man who spanned the decades of the 19th century that saw the birth of local radicalism, the growth of Trades Unionism and the development of the early socialist movement - and who only died in 1903, by which time what we know as today's Labour Party had been founded. Indeed, it can be said that Tweddell was unique in that he provided a local life-long link between Chartism, working class radicalism, involvement with the nascent workers movement and the beginnings of what we know as the modern Labour movement.

His story remains to be fully written up, but the Tweddell society, backed by the lineal descendents of his family, in particular the late Paul MarkhamTweddell, George's, great, great grandson and his widow, Sandra, exists to give the facts about his life as they are known, as well as Great Ayton writer and musician, Trev Teasdel, who has also been extremely diligent in researching and re-publishing on-line Tweddell's life and written essays, compositions and poetry. It is overwhelmingly largely from the written up work of both the society and Trevor that I append - with thanks and acknowledgement - the brief synopsis below.

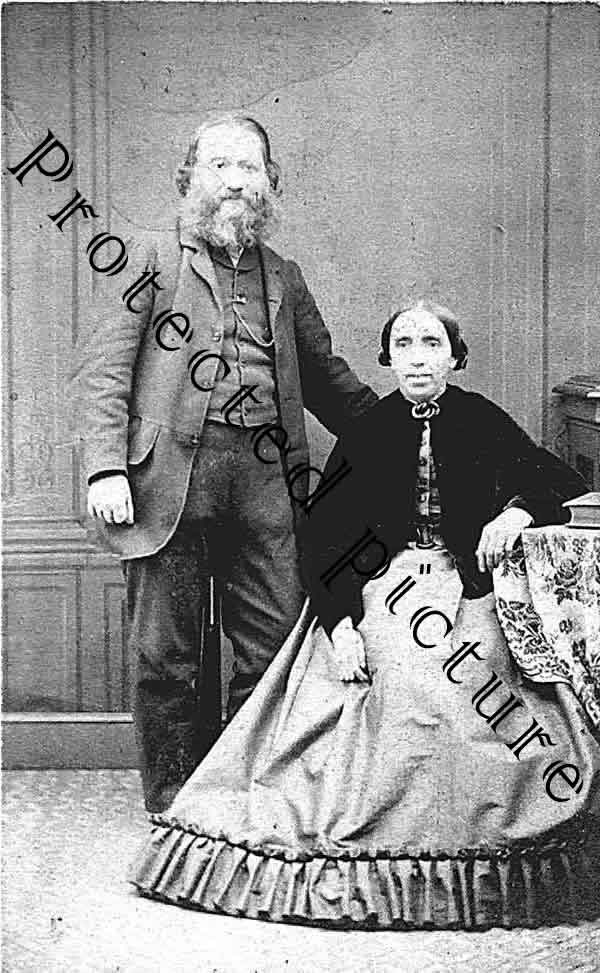

Paul Markham Tweddell R.I.P.

George was a native of Stokesley, born on a farm there in 1823. He was the son of Elizabeth Tweddell, whose extended family lived at Garden House, a 15-acre farm one mile along the Great Ayton road from Stokesley . George was born illegitimate although his fathers identity was never hidden - he was a Royal Navy Lieutenant, George Markham, who had been born in 1797 in the Rectory, Stokesley. Lt Markham had lived an adventurous life in the Royal Navy, had been mentioned in dispatches during the late Napoleonic campaign on the Mediterranean coast of France and was wounded in the Siege of Algiers in 1816.

However Elizabeth and her new born son were nurtured and cared for in the family, something not all that common in those days for children born outside marriage, It was also helpful that the family were part of the local middle class shopocracy, owning two businesses in Stokesley, a grocery shop in West Green and a drapers business run by his uncle.

Elizabeth's mother worked in her father's grocery shop and from an early age took George for walks around the district when time allowed during which she taught him all she knew of country lore. He was schooled at the local Stokesley National School, where he came into contact with an inspirational teacher, William Sanderson, who took him under his wing expanding the school's teaching with an informal education given around the countryside during fine evenings. These discussions built up the boy's knowledge of science, philosophy and history and he acquired a life-long love of literature, particularly for poetry.

It is probably also that at this time he developed his life long radicalism. Stokesley at this time was one of the biggest town in what was then the 'old' Cleveland. Middlesbrough had yet to be built, and the local economy was based on agriculture, agriculture which was largely based on the growing of flax, which was then spun and woven locally into linen - a key material in clothing, and, locally, sailcloth making for the large sail making enterprises in Stockton and Yarm.

Stokesley was also a town with a history of political radicalism in the period following the French Revolution and there was a flourishing Paineite movement active in the town, and which corresponded widely with similarly minded associate groups in Stockton and the wider North East. Many of the people from that period would have still been alive and active in Stokesley's town life, and I suspect George lapped up their anecdotes and observations. He could also not, as a boy, have been unaware of the unrest in the area following the economic downturn of the late 1820's and early 1830's and the subsequent agricultural depopulation caused by both that recession and the impact of the enforced enclosure of land by the local gentry. Indeed, it was nearby Yarm that marked the northernmost extent of the England wide 'Swing' riots of the 1830's and in which many agricultural labourers took part in - at the risk of their lives.

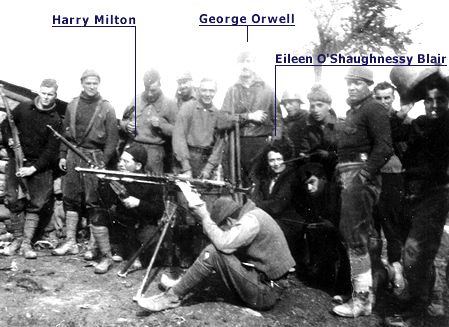

George in mid life

After leaving school, George worked briefly with his grandfather, John, and then became an apprentice to William Braithwaite who ran one of the two large printing and publishing companies in the town. Braithwaite had the reputation of supporting promising young employees and introduced George to John Walker Ord (1811-1854), the admired author of The History and Antiquities of Cleveland (1838). The two men became friends, despite their differing politics, and continued corresponding until Ord's death.

In 1841, at the extremely young age of 18, George sought approval from his master to set up a newspaper and his master agreed, in spite of the obviously radical tone George proposed ('to give the ordinary people of Cleveland a newspaper that would reflect their more liberal opinions rather than those of the landowning classes'). The first copy of the Cleveland News and Stokesley Reporter duly appeared on the 1st of November 1842,

A free press makes us free

The paper took a radical stance from the very first edition, and after two further editions had hit the streets and were beginning to be avidly read and passed around by local artisans and farmhands, it appeared that a determined attempt by local Tories to silence this new - and possibly dangerous - voice was mounted. It seems that representatives of the local propertied class visited Braithwaite to persuade him to stop publishing George's criticism of the Tory government, of which they were firm supporters. They demanded of Braithwaite that he was to withdraw from George the use of his printing press and the licence he needed to publish from the premises.

As a result the printer dismissed George (probably on the legal grounds of "bringing his master into disrepute"). Within a month, remarkably, George had managed to acquire a new license and access to a new press (although from whom is not known) to produce the third edition on time. For George, the contents for the editorial for this edition were obvious and he castigated his former employer, claiming Braithwaite was trying to 'crush our little periodical', and that 'our printer is a good easy man, afraid that our generous principles of peace on earth and goodwill toward men should be mistaken for his own'.

When it became obvious to his political opponents that George's newspaper was going to continue as an organ of anti-government opinion in the area, the opposition quickly put together a rival the Cleveland Repertory and Stokesley Advertiser, appearing on the same day as George's third edition, 1st January 1843.

Probably to George's bitterness this was also published by William Braithwaite using the capacity of his press left vacant by the departure of the Reporter. The rival's explicit policy was: 'to put right the failure of other sources of news and opinion in the area'; 'to uphold great national institutions, especially the Church of England' and '- amazingly - to be more 'uncongenial" to an agricultural population'. "We are," they concluded, "conservatives". The message was clear and stark. No workers need read it. No cottagers need buy it. It was for the local wealthy class and the continuance of the old order.

But George's bull-like tenacity ensured that his paper - a paper for everyman and women, not the estate owners - continued to hit the streets. His view of his new competitor was contemptuous.

"When the Stokesley News and Cleveland Reporter first made its appearance in the political and literary world, it was with a firm determination to lash every species of vice with an unsparing hand, and to be the unflinching advocate of civil and religious liberty - fearlessly to tear the mask from the sinister deeds of unprincipled legislators and trafficking politicians of every party."

From George's editorials in the Cleveland News and Stokesley Reporter it is possible to construct his political 'wish-list', wishes of which many came true. Of these some came quickly; the Corn Laws were repealed in 1846, the fall of Napoleon III in France two years later. Others took more time, arriving piecemeal like the abolition (in peacetime) of the cat-o'-nine-tails as a Royal Navy punishment in 1871, the 1870 Married Woman's Property Act and the beginnings of universal franchise (from 1884). Others were still issues alive in our time - Irish independence, the equal rights of women and the (still unresolved) abolition of the House of Lords.

The progress of the Anti-Corn Law league is reported and discussed throughout the collection of Stokesley News for 1843 / 44. These contemporary accounts of the action which eventually led to the repeal of the corn laws by Sir Robert Peel in 1846, although it brought his Government down, reflect the turbulent feelings of the times with their undercurrents of revolution. He also railed at the highly public "hiring fairs" for farm workers and domestic servants which were held in market towns like Stokesley and Guisborough with all the trappings of servility that they gave. Another topic featured was 'Ireland and its Rulers', with Daniel O'Connor advocating Ireland for the Irish. Politics were, however, overshadowed when the potato crop failed in 1845, to be followed by the disastrous famine. The New poor Law and its workhouse system was discussed at length: The People's Charter, What are the People to do? Is it a bloody revolution, or will bold writings true speaking and open acting prove the way?

In parallel with his newspaper activities George acted as secretary to the Stokesley branch of the Chartist Association and, when he was aged 23, shared the fate of many Chartist supporters by being imprisoned for contempt of court. Whilst inside, he wrote essays and poems later published in Chartist supporting periodicals These were a series on political themes, particularly about tyrants, oppression and people’s rights. He also, on release, began to play an active role in the local Freemasons which he had joined as a teenager .This may look odd now, but in the period we are speaking of, Freemasonry had a tradition of both encouraging free thinking philosophical thought and debate and allowing the space to develop these ideas untrammelled by conventional social restriction.

Edition 15 of George's newspaper, a year after his difficulties with Braithwaite, appeared on 1st January 1844 and in it he entered the announcement of his marriage to Elizabeth Cole on the previous day, 31st December 1843. Clearly the event had not been allowed to hold up publication, but what it had achieved was the bringing together of the families of three Cleveland personalities; George's grandfather, John Tweddell; his grandmother's brother, Christopher Rowntree ("Gentleman Kitty"); and Elizabeth's grandfather, Thomas ('Tommy') Cole, the stable master to Robert Chaloner, the chief landowner in Guisborough and whose descendent was to become the present Lord Gisborough (sic).

George and Elizabeth

After 23 editions of the paper the Reporter folded, (a demise probably brought about by the retreat of the Chartist tide) and, following this, George started putting his energies into writing and publishing more mainstream books and magazines. Amongst the latter (published by George's older half-brother, Thomas, also a former apprentice of Braithwaite) was Tweddell's Yorkshire Miscellany and Englishman's Magazine (1844-46) which John Ord encouraged by offering articles of his own for inclusion, proof-reading it and defending George from a similar, rival magazine being planned in Stockton on Tees.

It seems that this magazine had mixed fortunes and in the late 1840's both George and Elizabeth began to look to a new life departure. This was to bring them from the market town of Stokesley and the small (but burgeoning) industrial townships of Stockton and Middlesbrough to the very heart of the new industrial country that was developing new technologies and new class structures.

During the 1840's British industrial towns were experiencing the worst effects of the industrial revolution. Large families lived in destitution, with inadequate housing and frequent periods of unemployment. In 1850, the British government was alerted to these conditions through a report that recognised a correlation between those being convicted of crimes and their lack of education. By introducing children to reading and writing and by giving them the habits of working regularly, members of the council hoped children: "who had fallen into a life of crime could be persuaded to amend their ways" through 'Industrial Schools' set up by local initiatives.

If anywhere in Britain needed such institutions, it was the new town of Middlesbrough where, according to the historian, R.I.P. Hastings, social facilities were slow in developing due to the town's lack of leadership (except for the efforts of a handful of non-conformist churches). Inevitably, despite a willingness to be involved in the new Industrial School movement, Elizabeth and George had no convenient place in which to assist in Middlesbrough, which had to wait until 1875 for such a school of its own.

The 'Infant Hercules' - but no place for infants

In contrast the Lancashire industrial town of Bury, where crime was common despite the flourishing state of its cotton and iron industry, had swiftly heeded their town's need. By March 1855 prominent Bury people had pledged their support alongside the local police and were ready to set up and fund an Industrial School. So it was there that George, as headmaster, and Elizabeth, as matron, responded to a call made probably by Rev. Sidney Turner, the government inspector of reformatories, and Thomas Wright, the prison philanthropist with both of whom George had corresponded.

Being based in Bury meant that they were close to the new industrial giant 'shock city' of the nineteenth century, Manchester, a city that had recently been analysed by Engels for his book 'The Condition of the Working Class in England', and especially for George regular attendance at meetings of the Manchester Philosophical Society, a forum for debate on progressive and radical ideas of the age. This body, established in 1781 as the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester, by Thomas Barnes and Thomas Henry, had many prominent members including Robert Owen, John Dalton and, later scientists such as Ernest Rutherford and engineers like Robert Whitworth.

Of interest is the thought that there George could have met Friedrich Engels, who, after a period out of Britain, had returned to Manchester to again take up a position in the family firm, Ermen and Engels, after an exciting time observing and taking part, with Marx, in the revolutionary upheaval in the Europe wide unrest of 1848-9. True, Manchester was by then a big city, but the middle class literary and philosophical milieu there was still very small, and it is certain that this was a pool in which both George and Engels would have swum. Whether they met will always be unknown, but to me, the fancy that they did, remains.

Despite the wide support given to the school, notice was given in July 1860 that Bury Industrial School would close on 20th August without any apparent reason. The event that set the crisis underway appeared to be the departure of a Unitarian minister, Benjamin Glover, who had taken responsibility for the administration work of the school and raised funds. George was deeply disappointed by the decision and tried to set up another school on his own. In an open letter to the local newspaper he appealed for subscribers and offered to open a new school on the 1st September, accepting a lower salary than before and defraying any extra costs from his own income. Disappointingly, money did not materialise and the author of an article in the Bury newspaper in 1919 suggests Bury's leading citizens did not approve the private nature of this venture, as the school would no longer be in the control of the town authorities.

Reflecting thirty years later on this time, George wrote that he "enjoyed collecting abandoned children" in Bury, although Elizabeth had found the combined duties as matron to the school and mother to the growing family too onerous. The Tweddell family left almost at once even postponing the baptism of their latest child until they had found a new home back in Stokesley.

The next year saw another move when they upped sticks to live at the now demolished street, 11 Commercial Road, in Middlesbrough's St Hilda's area. At this time almost all the inhabitants of this town were labourers, which made George one of the very few people in the town to have status high enough to be worthy of note in Slater's 1864 Yorkshire Directory, George being one of the only two 'gentry' entered in it.

A family bequest (of £100 per year) helped George to look to new enterprise, and this took the form of a new business 'Tweddell and Sons', a newsagent and printing business based at 87 Linthorpe Road (now a new building occupied by Superdrug), One product of this new business was a Middlesbrough Directory, and a assorted booklets with a local flavour. As the printing and publishing business proceeded, George seems to have learnt from his earlier period and adopted a more cautious business strategy. This time a list of subscribers was set up before the heavier expense of printing was started. With a major book, a list of 300 subscribers seems to be the number sought before starting a print run, although a small book could make a profit with 100 subscribers. Only the preparation and editing remained a speculative cost to be borne by the business if the project failed.

In was in this period that George did most of his writing. These were, in the main, collections of poetry, sonnets and compositions (often in local dialect) by other local writers, local histories and a pioneering tourist guide to Redcar and East Cleveland, at the time being opened up to visitors by the new connections pioneered by the Stockton and Darlington Railway. This, whilst concentrating on the beauties of the area and local buildings of interest, also added social content and ideas for the development of Teesside - including the idea of making Redcar 'a harbour of refuge' linked to Middlesbrough and the new Middlesbrough Docks by a canal capable of allowing passage to sea going vessels and thus allowing them to avoid the then undredged sandbanks and shallows of the Tees estuary. His output in this period also allowed for Elizabeth to have published a collection of poems she had penned, and which appeared under the author's pseudonym of 'Florence Cleveland'.

He also engaged in extensive correspondence with other writers and radicals across the North East. This was a wide circle, including such people as Joseph Cowen, the Newcastle based editor of the Newcastle Chronicle, a one time MP and friend of, amongst others, Garibaldi and Bakunin. In one letter George declared "I could name a local writer for every tick of my watch."

This diligent and onerous work was his public legacy. His "People's History of Cleveland" was preceded by a history of the new town of Middlesbrough, and nearly a century on, this became the key primary source for Asa Briggs when he came to write the chapter on Middlesbrough in his pioneering work on urbanism "Victorian Cities". Much of his work of this time has been seen, perhaps inaccurately, as simply backward looking, ruralist and 'arcadian'. In this he was not alone as a radical. Much progressive thinking of this time also shared this nostalgia for a supposed golden age of rural harmony, untouched by the blight of industrialism - good examples being William Morris's 'Dream of John Ball' and the works of Ruskin. Indeed, we perhaps saw an echo of this in the dramatic speech of Winston Churchill (once an advanced Liberal) who saw a defeated Britain in 1940 as ushering in a new global dark age "made more protracted by the lights of a perverted science"

None the less, George also shared the seeming contradiction of many Victorian writers and radicals who both pined for that lost golden age, yet still saw the need to promote and advance the technological spirit of the age. In a passage in his history of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, George regretted the pollution of industry, with "clear rivulets running with the stinking refuse of dyehouses and factories and the wastes of towns" (a visual image he surely took from his time in Manchester and Bury) but, at the same time said that the railways, in their work of bringing people and communities closer together, were living proof of an adage of one of his heroes, Thomas Paine, in that they acted to "lose by degrees the awkwardness of strangers and the moroseness of suspicion, they learn to know and understand each other". In this he was at one with Marx and Engels who, writing at the same time, were able to both laud the technical advances that capitalism could give birth to, but at the same time seeing these advances as ones that could help liberate an urban working class to take what they, by their skills and labour, had produced,

George also found a substitute for writing editorials in his earlier newspaper, by adding political and social commentaries in the linking sections between articles by contributors. These showed clearly that his earlier Chartist spirit had not left him. For example, in an essay about the history of Liverpool, alongside a woodcut of its coat of arms, George takes the opportunity to comment on the evils of the city's involvement in the slave trade, using the nom-de-plume he reserved for such social ideas - Peter Proletarius (Peter of the Ordinary People), and by this strategy he aimed to not pull his punches - on Liverpool saying "When the offended player, George Frederick Cooke advanced to the footlights and told the burgesses of Liverpool, that 'the very bricks of their houses were cemented by the blood of the slave!' he acted no fictitious part, but boldly uttered a great truth, which must for ever leave an indelible stain of blood in the annals of Liverpool, which, like that on the hands of Macbeth, 'all great Neptune's ocean' cannot wash away, and 'all the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten'".

This strain of radicalism continued in later pamphlets where he looked back at his earlier life against the backcloth of struggles against reaction and George's involvement in political meetings and agitation (with threats from Tory opponents) and comments arising from contemporary meetings with workers attending his lectures at Mechanics Institutes.

Clearly George was a central character on the radical political scene in those times, This comes not only as a result of the obvious influence of his newspaper in the 1840s, but also from the political support he gave to the development of trades unions among local ironstone miners toward the later years of his life.

George knew from personal experience that Stokesley and the villages surrounding Middlesbrough during the second half of the nineteenth century, were unlike now, not rural boltholes for a wealthier class, but places where many lived in slum dwellings and squalid yards and tofts running up from the main street (Guisborough was notorious for such squalid accommodation) and where financial decline and depopulation was endemic as a result of the national deterioration in agriculture and a shift in local trade from rural to urban locations. As for the countryside surrounding these villages, this was fast becoming an anthill for the extraction of ironstone, iron ore, jet and alum along a long swathe of land from the flanks of Roseberry Topping along to the high cliffs of Boulby and Saltburn.

The Tweddells were well aware of this new world on a highly personal basis, as two of their daughters married men who became ironstone miners shortly after marriage. One, son-in-law, Robert Watson, was originally a butcher and from a family of yeoman stock who had farmed in Rosedale but who was forced away from his home to work at a mine near Skelton Green, and the other, Thomas Turner, ended up labouring at another mine at nearby Brotton. Robert Watson's older brother (an agricultural worker) also moved from Rosedale with his family and settled in New Skelton. Son Tom Cole Tweddell, too, had two brothers-in-law in the mining industry. Both had been agricultural workers but moved away to the mines, one to an ironstone mine above Ingleby Arnside, the other to a pit in the southern area of the Durham coalfield.

There were also mining links from grandchildren. Three of Robert Watson's daughters (i.e. George and Elizabeth's granddaughters) married the sons of miners after their grandparents' deaths to men they had met as children in Skelton Green in the 1880s. These men's fathers had originated from a variety of places; one enticed from North Norfolk (a shepherd), another from West Cornwall (a tin miner), and the third was a local agricultural labourer. Thus George had every reason to visit the East Cleveland area on a regular basis, and in doing to see the reality of daily life for the miners and their families for himself, and, from that, to involve himself in their struggles.

In this connection it is interesting that the Brotton and Skelton Miners were amongst the first to embrace Trade Unionism (and with their comrades in Eston) to take explicit socialist and republican stances which were reflected in the setting up of republican clubs and the use of Union funds to underwrite wider political activity in the district. It is, I believe, not at all fanciful to surmise that George's influence and knowledge had struck root here - he was, after all an accomplished lecturer and orator, and he never lost those skills

George's later years were spent back at the family home in Stokesley, Rose Cottage. There was poor health in the family, and in 1899 Elizabeth died aged 75 whilst being cared for in the Stokesley Workhouse (now Springfield House), under what what now would be called 'respite nursing'. The reports of her funeral conducted in the chapel in the New Cemetery appeared in the newspaper and mentioned the severe snowstorm that prevented many of her admirers from attending. George died on 31st November 1903 aged 80 and was buried beside his well-loved wife in the South Eastern corner of the New Cemetery. In the cortege his body was carried from Rose Cottage towards his birthplace, Garden House; along the same route his mother had carried him back from his baptism 80 years before. Unfortunately, no account of his funeral has yet been found, but family tradition has it that many prestigious local and regional dignitaries as well as many relatives, joined in the funeral procession, while another tradition says the Odd Fellows present undertook a Masonic style service by the grave in George's honour. There was little evidence of a religious element in the service, judging by the reports, although one obituary suggested that towards the end of his life he leant towards Unitarianism, whose creed which rejected doctrines such as original sin and predestination, would have certainly have appealed to him and to his belief of the abilities of ordinary people to build a better world for all.

![]()

Rose Cottage, Stokesley

George did leave much written material and this would have been invaluable in decoding and chronicling his life and times. From this websites perspective, they would have been crucial in seeing exactly how his Zelig like existence, with the unique knack of always being on the scene at important times, meshed with his relationship with emerging socialist and radical thought - from Chartist times right through to a period when the Labour Party had become established and the local Cleveland Miners Association had embedded itself as a political power in this area. Alas, this was not to be, as a disastrous flood following the bursting of the banks of the Rover Leven engulfed Rose Cottage, with his papers lost beyond retrieval.

George and Elizabeth's grave

However, it is clear that George was someone whose DNA still runs in our genes and for his dedication, work, argument and activity for a better, more equal and democratic Teesside, we all owe him an ancestral debt.

David Walsh

Authors notes. If readers want to know more about Tweddell's life and career, there are two extensive website hubs. One, the Tweddell hub, gives links to on-line editions of much of Tweddell's published work. See http://georgemarkhamtweddell.blogspot.co.uk/p/archives.html The other, The Tweddell history site, set up by members of the Tweddell family, hosts a detailed biography and also links to much of Tweddell's poetry. See http://www.tweddellhistory.co.uk/

.png/300px-Spanish_War_Children_(restored).png)